Imagine a Victorian drawing room adorned with an imposing canvas: a gigantic, almost rectangular cow, perched on slender legs, looking as if it’s about to swallow a village. This is much more than a work of art: it’s a visual manifesto of power, wealth… and a certain aristocratic sense of humor. Welcome to the curious world of nineteenth-century cattle portraitsᵉ in England.

A race to fatten cattle

In 19th century England, landowners didn’t just breed their cattle : they ” improved “ them. Better fed, sometimes fertilized… their cows reached exceptional proportions. Some noble farmers presented themselves as “benefactors”, arguing that if they could fatten gargantuan beasts, it would pave the way for greater productivity for modest farmers, thus improving national food security

Engraving by William Ward (1766-1826), Portrait of the short-horned bull Patriot, 1810, Yale Center for British Art

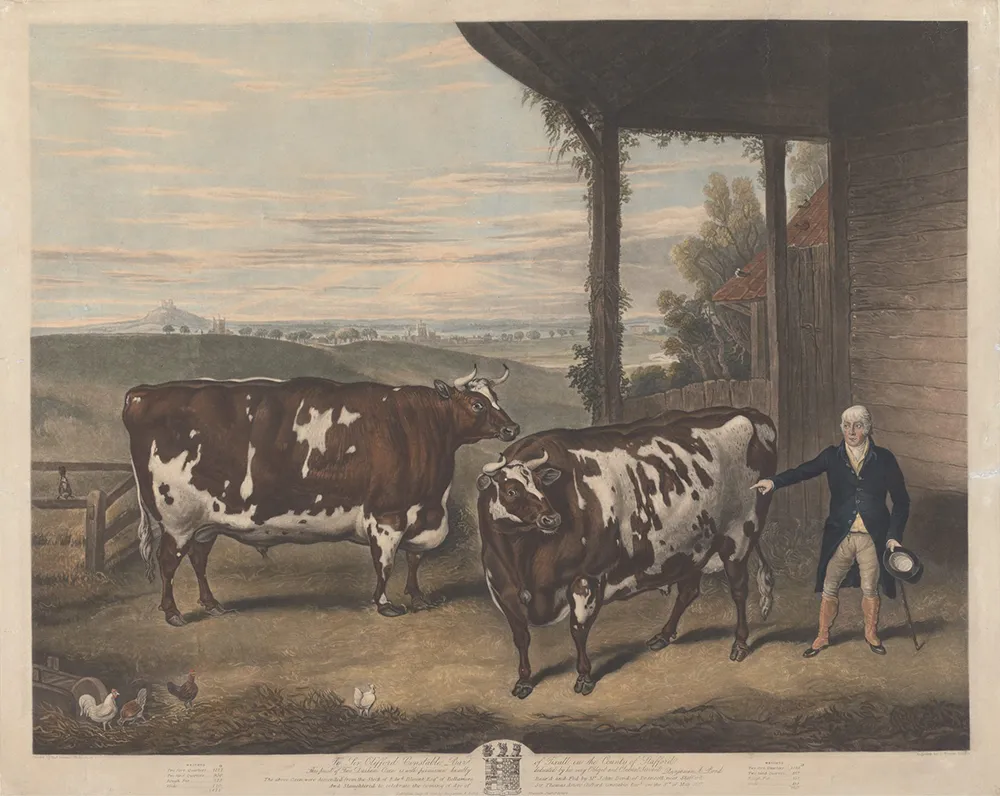

A telling example: improvers considered themselves patriotic, convinced that their quest for heavier breeds benefited the rural community and the country as a whole. Proud of their achievements, they commissioned paintings depicting them and their cattle.

The most famous example is probably the Durham ox. Weighing in at 3,000 pounds, this bull attracted crowds, raked in agricultural prizes, and printed reproductions of a painting depicting it sold out by the thousands !

Animal portraiture as an extension of aristocratic portraiture

Traditionally, the British elite commissioned ceremonial portraits to affirm their rank: court painters and academicians depicted the idealized features of landowners. In the 19th century, this logic shifted to the agricultural world: animals themselves became subjects worthy of portraiture.

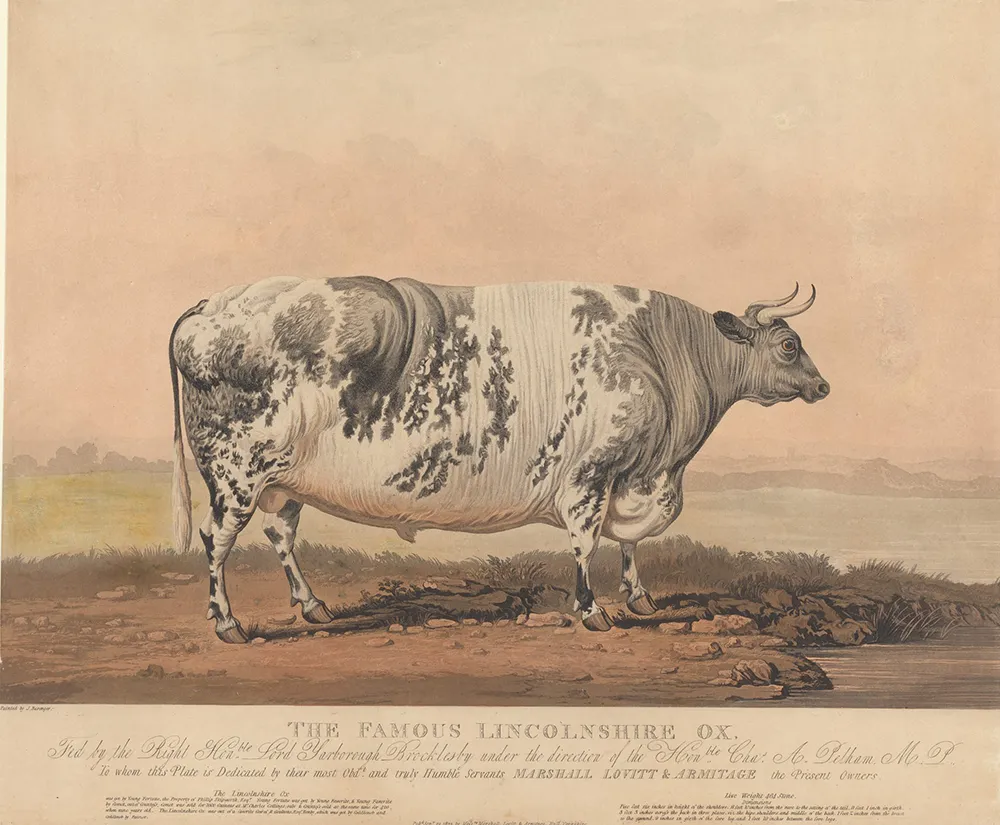

The parallel is obvious: profile framing, monumentality, hieratic pose. The animal almost takes the place of the master, condensing prestige and fortune.

Gradually, exaggeratedly shaped portraits of cows, sheep and pigs began to appear. These images, halfway between caricature and official painting, reveal a little-known part of British art history. They reflect both the picturesque taste of the time and the social ambitions of the commissioners.

James Ward, 1769-1859, Gloucestershire Old Spot, between 1800 and 1805, Yale Center for British Art

Animals were often depicted in profile, with stylized silhouettes: cows became cubic, sheep oval, pigs… rolling balloons! These shapes evoke both the density of the flesh and the technical mastery of the breeder. These portraits also served as didactic or promotional images, accompanied by information such as the animal’s measurements, pedigree and name. They were published in agricultural magazines and sold as show souvenirs.

A naive but codified style

At first glance, these paintings may seem clumsy: cubic proportions, exaggerated fat masses, tiny legs supporting hypertrophied bodies. But this aesthetic is not the result of technical ignorance, it obeys a precise codification: to visually emphasize the “ideal” qualities of the animal, accentuating volumes as symbols of power were once accentuated in royal portraits.

The exaggeratedly square shape of the animals also met the requirements of the cattle shows, which were looking for wrinkle-free hides and taut breasts…

Aesthetic reception and posterity

These livestock portraits occupy an ambiguous position in art history. They are part of a rural tradition, often painted by provincial or itinerant artists, far removed from London’s academic circles.

But their distribution (through engravings, lithographs, breeding catalogs) also makes them part of a mass visual culture, already heralding the logics of industrial image reproduction. In this sense, they are both ceremonial portraits and utilitarian documents.

Today, these paintings are no longer a sign of prosperity or patriotism, but appear so bizarre as to be hilarious. Yet engravings of these animals can still be found in pubs and inns, evoking a rural past. Some British pubs are even named after high-profile cows such as ” The Durham Ox “.

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel